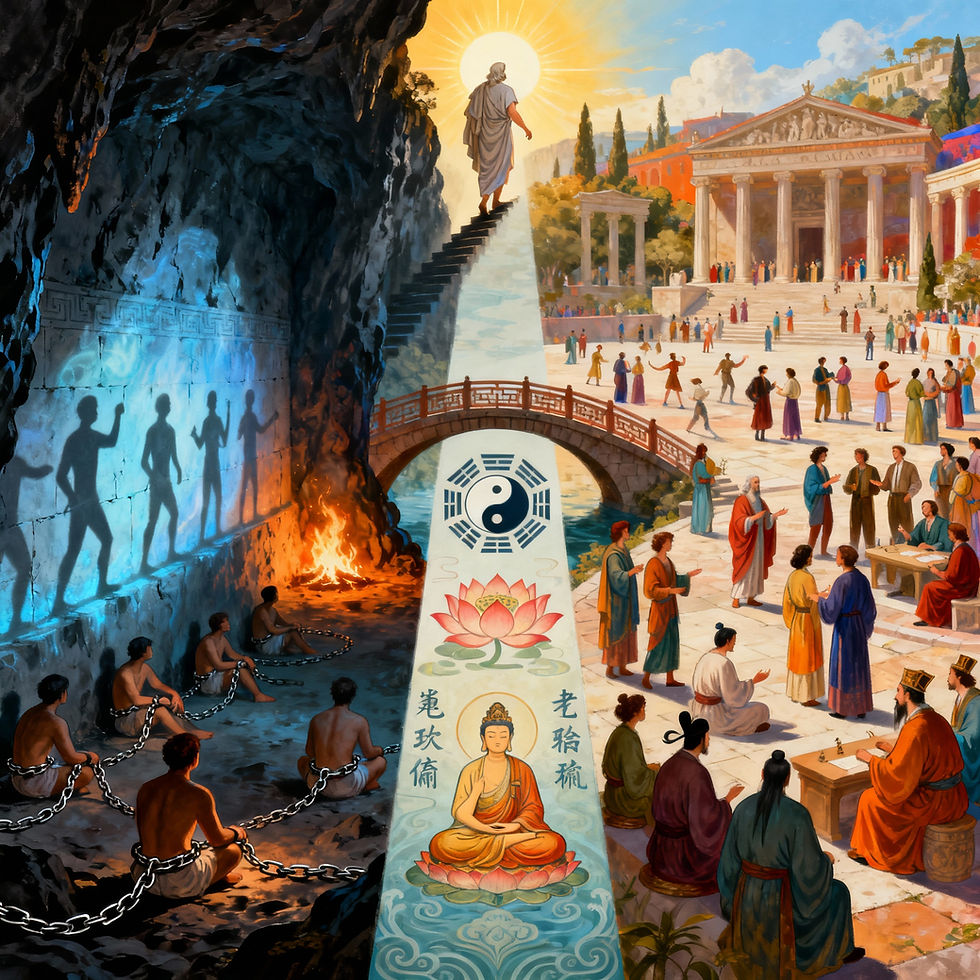

Between the Cave and the Tao: Contemplation and Action in Western and Eastern Philosophy — A Comparative Analysis of Plato, Hannah Arendt, and Asian Traditions

- Sérgio Luiz de Matteo

- Dec 7, 2025

- 35 min read

Updated: Dec 8, 2025

Abstract

This essay undertakes a comparative and critical analysis between two fundamental paradigms of Western philosophy — the vita contemplativa (bios theoretikos), as established by Plato, and the vita activa, as phenomenologically rehabilitated by Hannah Arendt — investigating how these traditions structure the relationship between thought and action. The study examines the ontological hierarchy that has traditionally subordinated political action to the contemplation of eternal truth in the West, analyzing how Plato grounds the primacy of the intelligible over the sensible and how Arendt seeks to rescue the dignity of the public sphere and human plurality. Through the dissection of Arendtian categories of labor, work, and action, contrasted with Platonic metaphysics of the Forms and the figure of the philosopher-king, the article demonstrates that the tension between these models is not merely methodological but anthropological, reflecting divergent conceptions of freedom, immortality, and the purpose of human existence.

Crucially, the essay expands this Western analysis by engaging with transcultural perspectives, exploring how Eastern traditions — particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism — offer alternatives to the Western hierarchical dichotomy. While the West has tended to structure contemplation and action in an exclusive relationship, Asian traditions often seek their integration or transcendence. Indian Karma Yoga, the Bodhisattva ideal in Mahayana Buddhism, the concept of Wu Wei in Taoism, and the inner virtue of the Junzi in Confucianism represent ways of life that do not radically separate thought from action, suggesting that the Western dichotomy is not universal but a specific product of dualistic metaphysics. The essay concludes by discussing the contemporary relevance of this Western-Eastern dialectic in the face of the crisis of the modern public sphere and the possibility of less hierarchical syntheses between contemplation and action.

Keywords: Hannah Arendt; Plato; Active Life; Contemplative Life; Political Philosophy; Transcultural Perspectives; Ontology; Taoism; Buddhism; Hinduism.

1 Introduction

The history of Western political philosophy can largely be read as the history of a hierarchy. From the foundation of classical metaphysics in ancient Greece, an axiological primacy of stillness over movement, of the eternal over the transitory, and consequently of contemplation (theoria) over action (praxis) was established. Hannah Arendt, in her seminal work The Human Condition, identifies in Plato the inaugural moment of this tradition, which, according to her, degraded the dignity of politics by attempting to subject it to standards of certainty and fabrication (ARENDT, 2010). This hierarchization shaped centuries of Western political thought, establishing a structure in which rational knowledge and eternal truth should guide — and subordinate — contingent human affairs.

The objective of this essay is to critically distinguish between the Arendtian vita activa and the Platonic vita contemplativa, not merely as historical categories, but as expressions of two fundamentally different anthropologies. It is not just a matter of opposing "doing" to "thinking," but of understanding how each philosopher situates the human being in the world and what the purpose of their existence is. For Plato, politics is often seen as a "cave" of shadows from which the philosopher must escape to reach the truth (PLATO, 2001); for Arendt, politics is the only space where freedom can appear phenomenally (ARENDT, 2010). This divergence is not merely theoretical: it has profound implications for how we understand citizenship, political responsibility, and the meaning of human life.

We will first analyze the dichotomy between the vita contemplativa (bios theoretikos) and the vita activa (bios politikos), which constitutes one of the structuring axes of the Western philosophical and political tradition, delineating not only distinct modes of existence but also axiological hierarchies that have defined, over the centuries, the purpose of human life and the organization of the city. The analysis of these categories transcends mere individual choice, reflecting ontological tensions about the relationship of man with the divine, with truth, and with the political community. The relevance of this discussion remains undeniable, as understanding Western thought requires scrutiny of how different eras articulated the primacy of acting over thinking, or vice versa, shaping conceptions of citizenship, virtue, and happiness.

Next, we will proceed to the anatomy of the vita activa in Arendt, highlighting the fragility and greatness of action. After that, we will return to Plato's bios theoretikos, exploring the intellectual asceticism necessary for access to the Forms. Finally, we will establish a critical confrontation between these views, elucidating how Arendt's proposed hierarchical inversion does not aim to annul thought but to protect human plurality from the tyranny of a single Truth applied to human affairs.

However, this essay goes beyond purely Western analysis. Recognizing that the dichotomy between contemplation and action may be a specific product of Western dualistic metaphysics, we will explore transcultural perspectives that offer significant alternatives. Eastern traditions — particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism — have thought about the relationship between contemplation and action in radically different ways, often seeking their integration rather than hierarchization. Indian Karma Yoga proposes disinterested action as an expression of contemplative wisdom; the Buddhist Bodhisattva chooses to remain in the world out of compassion after achieving enlightenment; the Taoist sage acts without acting, in perfect harmony with the natural flow; and the Confucian Junzi orders society through inner virtue cultivated. These figures represent ways of life that challenge the Western dichotomy, suggesting that other syntheses between thought and action are possible and, perhaps, necessary to address contemporary political challenges.

The relevance of this transcultural comparison is twofold: first, it allows us to understand the Western tradition not as universal but as culturally specific; second, it offers conceptual resources to think beyond the Platonic hierarchization that continues to structure modern politics, particularly through technocracy and the subordination of democratic deliberation to specialized expertise. By engaging with these traditions, we do not seek superficial syncretism, but a deeper understanding of how different cultures responded to the fundamental problem of how to live — a problem that remains urgent and unresolved.

2 Contemplative Life vs. Active Life: Philosophical Roots

Regarding the vita contemplativa, its most robust philosophical roots are found in Classical Greece, where the activity of the intellect (nous) was often associated with the divine and the eternal. If Plato established the contemplation of the Forms as the pinnacle of existence, it was Aristotle who systematized the superiority of the theoretical life in the Nicomachean Ethics (ARISTOTLE, 2001). For the Stagirite, supreme happiness (eudaimonia) resides in the activity of the soul in accordance with the most excellent virtue, which is philosophical wisdom (sophia).

Aristotle (2001, p. 237) argues that contemplative activity is the most continuous, the most pleasurable, and the most self-sufficient, likening man to the gods, for "it is not as man that he will live in this way, but insofar as there is something divine in him."

This primacy of contemplation was absorbed and transmuted by the medieval Christian tradition, where the Greek bios theoretikos converged with the monastic ideal and the pursuit of visio beatifica. Thomas Aquinas, in the Summa Theologica (2005), reaffirms the superiority of the contemplative life over the active one, maintaining that the former deals with divine things and the latter with human ones. However, Aquinas (2005) introduces a vital nuance by suggesting that preaching and teaching — fruits of contemplation transmitted to others — represent a mixed and exalted form of life, although the ultimate end remains the knowledge of God. In this context, virtue and happiness become partially detached from worldly political realization to fix themselves in transcendence.

In contrast, the vita activa has a trajectory that traces back to the dignity of the polis and resurges with vigor in civic humanism and republicanism. In the Greco-Roman tradition, especially in Cicero (2018), the active life was not merely labor or production, but virtuous engagement in public affairs (res publica). Political action was the stage where virtue manifested visibly. Cicero (2018, p. 45), in On the Republic, criticizes those who retreat into speculative idleness at the expense of civic duty, stating that "the existence of virtue depends entirely on its use, and its principal use is the government of the city."

The Renaissance marked a radical revaluation of the active life, contesting the supremacy of monastic isolation. Thinkers like Machiavelli reclaimed the notion that human greatness is forged in history and political interaction. Machiavellian virtù is eminently active, requiring the capacity to confront fortune and shape the destiny of the political community. In this spectrum, citizenship and the common good cease to be byproducts of cosmic order to become achievements of deliberate human action.

Arendt (2010) observes that this tradition saw political participation not as a burden, but as the very actualization of freedom, distinguishing itself sharply from the modern conception that tends to reduce human activity to productive labor.

The relationship between these two modes of life, however, is marked by both tension and complementarity. Historically, political philosophy has oscillated between the ideal of the philosopher who isolates himself to reach the truth and the citizen who sacrifices himself for the city. Aristotle, despite elevating contemplation, recognized that political life was necessary to create the conditions of peace and order that make philosophy possible. There is, therefore, a functional interdependence: the city needs wisdom to be just, and wisdom needs the city to exist.

In sum, the analysis of Western philosophical and political theories reveals that the duality between contemplative life and active life is not a mere classification of occupations, but the reflection of a profound anthropological tension about human destiny. While the Platonic-Aristotelian and medieval tradition tended to situate full realization outside the political cave or in divine transcendence, the republican and humanist tradition insisted that humanity is realized "among" men, in the construction of the common world. A critical understanding of this dialectic is fundamental for diagnosing contemporary challenges, where the recovery of an authentic active life, informed by critical reflection, presents itself as a condition for the preservation of political freedom.

3 The Active Life in Hannah Arendt: The Dignity of the Public Sphere

Hannah Arendt does not propose a political philosophy in the traditional sense of prescribing the best form of government; she performs a phenomenology of fundamental human activities. For Arendt, the philosophical tradition, traumatized by the trial and death of Socrates, turned its back on the instability of the polis, seeking refuge in the security of eternal ideas. Her task, therefore, is to "think what we are doing" and to unpack the vita activa into three distinct components: labor, work, and action (ARENDT, 2010).

3.1 Labor (Animal Laborans)

Labor corresponds to the biological process of the human body. It is the activity linked to vital necessity, survival, and the reproduction of life. Labor is cyclical and impermanent; its products are made to be consumed immediately. In Arendt's view (2010, p. 106), when labor ascends to the public sphere — as occurs in modernity, where the economy (the management of the household, oikos) becomes the central concern of politics — we become a society of animal laborans, where freedom is sacrificed in the name of abundance and consumption.

3.2 Work (Homo Faber)

Unlike labor, work is the activity that corresponds to the non-natural aspect of human existence. It is the fabrication of an artificial world of things, distinct from the natural environment. The homo faber builds walls, laws, institutions, and useful objects that confer stability and durability on human life (ARENDT, 2010, p. 167). Work creates the "world" where politics can happen, but it is governed by the instrumental logic of means and ends, which, according to Arendt, is dangerous when applied to politics, as it tends to treat men as material to be shaped.

3.3 Action and the Public Sphere

Action is the only activity that occurs directly among men, without the mediation of things or matter. It is the central category of Arendtian politics.

"Action, the only activity that is exercised directly among men without the mediation of things or matter, corresponds to the human condition of plurality, to the fact that men, and not Man, live on Earth and inhabit the world." (Arendt, 2010, p. 9)

Action has fundamental characteristics:

Plurality: Politics is based on the fact that we are all equal (as humans), but each one is unique (distinct). Without this distinction, action and discourse would be unnecessary.

Spontaneity and Natality: Acting is taking the initiative, starting something new. Arendt contrasts mortality (the focus of metaphysics) with natality (the focus of politics). Each birth is the promise of a new beginning, the capacity to interrupt the automatism of natural and historical processes.

Unpredictability and Irreversibility: Once initiated, action unleashes processes whose outcomes are unpredictable and cannot be undone. To deal with this, the public sphere relies on the faculties of forgiveness (for irreversibility) and promise (for unpredictability) (ARENDT, 2010, pp. 311-12).

Arendt warns of the risk of the loss of action in modernity. Bureaucratization and the rise of the social tend to convert action into behavior, replacing political freedom with the statistical administration of vital needs. As Benhabib (2000) notes, Arendt's analysis of the vita activa offers a profound critique of the modern reduction of politics to administration, rescuing the dimension of freedom and creativity that characterizes genuine action.

4 The Contemplative Life in Plato: The Supreme Quest for Truth

To understand the vita contemplativa in Plato, we must move away from the modern reading that sees theory merely as a stage toward practice. For classical Greek thought, contemplation (theoria) was a superior, self-sufficient, and divine mode of life.

4.1 The Ontology of the Forms and the Soul

In dialogues such as the Phaedo and The Republic, Plato establishes a clear dichotomy. The sensible world, accessible to the senses and where everyday politics occurs, is the realm of becoming (gignesthai), of constant change and opinion (doxa). True reality resides in the intelligible world of the Forms (Eidos), which are eternal, immutable, and perfect.

The human soul (psyche) is akin to the Forms. Philosophy is described in the Phaedo as a "training for death" (melete thanatou), that is, a constant effort to separate the soul from the distractions and passions of the body, allowing the intellect (nous) to contemplate naked truth.

4.2 The Cave and the Philosopher-King

The Allegory of the Cave (Book VII of The Republic) is the ultimate illustration of the tension between contemplation and politics. The philosopher is the one who frees himself from the chains (prejudices and shadows of doxa) and performs the periagoge (the turning of the soul), ascending painfully to the contemplation of the Sun (the Idea of the Good) (PLATO, 2001).

The ideal life, for Plato, is to remain in this contemplation. However, the return to the cave to govern is not merely a punishment imposed on the reluctant philosopher, but a moral duty that he must fulfill for the benefit of the city.

"Unless philosophers rule in the cities... there will be no respite from the evils of the cities, nor, I think, for those of the human race." (PLATO, 2001, p. 255 [473d])

This formulation reveals a crucial tension: although contemplation is ontologically superior, the philosopher's political responsibility is inescapable. The philosopher does not govern because he desires to, but because the justice of the city demands it. Thus, politics is not simply rejected, but subordinated to a standard of truth that must guide it.

It is important to recognize that this Arendtian interpretation, though profound and influential, is a specific reading of Plato and does not represent a consensus in the secondary literature.

Commentators like Gregory Vlastos (1991) and C. D. C. Reeve (2004) offer alternative interpretations that nuance this narrative of "traumatic escape." Vlastos, in particular, argues that Plato does not completely reject political action, but seeks to ground it in rational and ethical principles. Reeve, in turn, emphasizes that Plato's theory of justice is not merely contemplative, but prescriptive for political organization. Monique Dixsaut (2003) offers an even more nuanced reading, showing how Platonic dialectic involves a continuous movement between the intelligible and the sensible, not a simple rejection of the latter. In particular, Plato's Apology presents Socrates as someone who acted morally by refusing to escape, suggesting that Plato did not completely reject political action, but sought a different form of engagement. Moreover, texts like the Laws reveal that Plato proposed a detailed political regime that was not merely contemplative. These considerations do not invalidate Arendt's critique, but indicate that the relationship between Plato and politics is more complex than a simple rejection.

Here lies the crucial point: for Plato, politics must be shaped in the image of the eternal Truth contemplated by the philosopher. Political techné consists of applying the immutable standard (paradeigma) of the Forms over the unstable matter of human relations. Politics is subordinated to philosophy; action is subordinated to contemplation. The goal is to cease the chaotic movement of politics and establish an order that mimics eternity.

5 Critical Distinction: Values, Objectives, and Contexts

The distinction between Arendt and Plato is not merely a personal preference, but an ontological divergence about where the meaning of human existence resides.

5.1 Truth (Aletheia) vs. Opinion (Doxa)

Plato: Doxa is error, illusion, the shadow on the wall. The goal of life is to transcend doxa to achieve episteme (true knowledge). Politics based on opinion is pathological (PLATO, 2001).

Arendt: Rehabilitates doxa. For her, rational truth (mathematical or scientific) is coercive; it does not admit debate (2+2=4 is not a matter of discourse). Politics, however, deals with the world as it appears to me and to others (dokei moi). Doxa is the understanding of the world from a singular position. Politics is the confrontation and exchange of these plural opinions, not the imposition of a single Truth on human affairs. Crucially, Arendt differentiates doxa (legitimate opinion) from organized lying and totalitarian manipulation. Factual truth — the concrete facts of the world — constitutes the indispensable ground upon which politics rests. Without common facts, no common world is possible (ARENDT, 2009). Thus, while Arendt rehabilitates doxa as a legitimate space for political deliberation, she does not abandon factual truth as a necessary foundation for shared action. As Honig (2007) notes, this Arendtian rehabilitation of doxa represents a democratic alternative to Plato's pursuit of absolute truth, without, however, falling into relativism.

5.2 The One vs. The Many

Plato: Seeks Unity. Justice is One. The Good is One. Plurality and conflict are signs of disease in the city. The ideal State is the one that most closely resembles a single organism, where "friends have all things in common" (PLATO, 2001).

Arendt: Celebrates Plurality. Politics exists only because men are plural. Attempting to reduce plurality to unity (as in totalitarianism or technocracy) is to destroy the very condition of politics. Forced "union" eliminates the "in-between" space necessary for action (ARENDT, 2010).

5.4 Fabrication vs. Action

Plato: Conceives politics under the model of fabrication (poiesis). The philosopher-king acts as a craftsman (demiurgos): he contemplates the ideal model (the Forms of Justice and the Good) and tries to imprint that form on the passive matter of the city and the souls of citizens. In this conception, violence is justified as a necessary means to shape raw matter into a perfect work. The political relationship becomes one of command and obedience, analogous to the relationship between master and slave, or between the intellect that designs and the hand that executes. The goal is to produce a stable and lasting final result, eliminating unpredictability (PLATO, 2001).

Arendt: Vehemently rejects the application of the logic of fabrication to politics. For Arendt, politics has no "final product" or external "end" to itself; the end of politics is the very activity of acting and deliberating together. Treating politics as fabrication (social engineering) destroys freedom, as it implies that some know (experts/rulers) and others merely execute. Action is fragile, unlimited, and unpredictable; attempting to control it through a technocratic or Platonic model is to replace political life with bureaucratic administration (ARENDT, 2010, p. 276).

Arendt's central critique of the Platonic tradition lies in the identification of a fundamental rupture: the attempt to escape the fragility inherent in human affairs through the subordination of politics to philosophical standards. For Arendt, Plato, traumatized by the condemnation of Socrates, concluded that the polis was not a safe place for the philosopher and that persuasion (peithein) — the essence of political discourse — was insufficient against the ignorance of the multitude. Plato's response was the introduction of a tyranny of truth over opinion.

Arendt (2009, p. 143) argues that Plato replaced the experience of action (praxis) with the experience of fabrication (poiesis). In genuine political action, the outcome is unpredictable and there is no single author, as it occurs in a web of plural relations. In fabrication, however, there is a master (the craftsman) who holds the image of the final product (eidos) and shapes passive matter according to that model. By applying this logic to the city, Plato transforms the philosopher-king into a craftsman and citizens into human matter to be shaped. Arendt denounces this operation as the destruction of politics, as it eliminates plurality in favor of a coercive unity:

"The substitution of acting by making and of the political by the productive is the degradation of politics into a means to achieve a higher end — in Plato's case, the possibility of philosophy." (ARENDT, 2010, p. 276)

This subordination manifests itself in the redefinition of the concept of government. Arendt notes that, in Greek, the verb archein meant both "to begin" and "to lead." In the Platonic conception, a split occurs: the ruler is the one who "begins" (initiates command through knowledge of the Forms), but does not need to "act" (execute), leaving execution to the subjects. Thus, the distinction between rulers and ruled is born, which for Arendt is a pre-political category, typical of the domestic sphere (oikos), where the head of the family commands slaves (ARENDT, 2010, p. 234).

Therefore, Arendt's critique points out that Plato's "solution" to the evils of politics was, in fact, its abolition. In seeking stability and eternal truth, Plato tried to transform politics into a techné (technique/art), where the expert holds the monopoly on decision-making. This represents, for Arendt, the loss of the dignity of the public sphere, as freedom does not reside in the execution of a plan preconceived by philosophical wisdom, but in the spontaneous capacity of equal men to initiate something new and unforeseen in the world.

5.4 Immortality vs. Eternity

The final distinction lies in the relationship with time.

The Active Life (Arendt): Seeks earthly immortality. The Greek polis was the space of organized memory, where the extraordinary deeds and words of men could be saved from oblivion and the futility of the biological cycle. Politics is the human attempt to create something permanent in a world of mortals (ARENDT, 2010).

The Contemplative Life (Plato): Seeks eternity. The philosopher's experience with the Forms occurs outside of time and space. Eternity is the nunc stans (the permanent now), ineffable and incommunicable. For the Platonic philosopher, the pursuit of political fame or historical memory is vanity, as true being is eternal and does not need human validation (PLATO, 2001). However, it is important to note that Plato also recognizes political immortality as an inferior form of perpetuation; the philosopher's soul, in contemplating the Forms, participates in an eternity that transcends any historical memory.

The tension between these two forms of permanence — earthly immortality through memory and transcendent eternity through contemplation — reflects divergent conceptions not only of time, but of the very nature of reality and human value.

6 Points of Tension, Convergences, and Contemporary Relevance

The relationship between the vita activa and the vita contemplativa is not merely one of opposition, but of a dialectical tension that defines the limits of Western civilization.

6.1 The Socratic Trauma and the Flight from Politics

Arendt argues that Plato's political philosophy is born from a trauma: the trial and execution of Socrates by Athenian democracy. The death of the most just man by the polis convinced Plato that persuasion (peithein) and opinion (doxa) were unreliable. The vita contemplativa thus emerges as a fortress: an attempt to find an absolute (Truth) that could coerce the multitude and make the city safe for philosophy (ARENDT, 2010).

However, it is important to recognize that this Arendtian interpretation, though profound and influential, is a specific reading of Plato and does not represent a consensus in the secondary literature. Commentators like Gregory Vlastos (1991) and C. D. C. Reeve (2004) offer alternative interpretations that nuance this narrative of "traumatic escape." Vlastos, in particular, argues that Plato does not completely reject political action, but seeks to ground it in rational and ethical principles. Reeve, in turn, emphasizes that Plato's theory of justice is not merely contemplative, but prescriptive for political organization. Monique Dixsaut (2003) offers an even more nuanced reading, showing how Platonic dialectic involves a continuous movement between the intelligible and the sensible, not a simple rejection of the latter. These considerations do not invalidate Arendt's critique, but indicate that the relationship between Plato and politics is more complex than a simple rejection.

The tension lies here: to make the city safe, Plato had to abolish politics (understood as free debate among equals) and establish government by truth. Arendt attempts to reverse this movement, arguing that the tyranny of Truth (whether religious, scientific, or ideological) is the end of human freedom.

6.2 The Subordination of Politics to Philosophy: From Praxis to Poiesis

Arendt's central critique of the Platonic tradition lies in the identification of a fundamental rupture: the attempt to escape the fragility inherent in human affairs through the subordination of politics to philosophical standards. For Arendt, Plato, traumatized by the condemnation of Socrates, concluded that the polis was not a safe place for the philosopher and that persuasion (peithein) — the essence of political discourse — was insufficient against the ignorance of the multitude. Plato's response was the introduction of a tyranny of truth over opinion.

Arendt (2009, p. 143) argues that Plato replaced the experience of action (praxis) with the experience of fabrication (poiesis). In genuine political action, the outcome is unpredictable and there is no single author, as it occurs in a web of plural relations. In fabrication, however, there is a master (the craftsman) who holds the image of the final product (eidos) and shapes passive matter according to that model. By applying this logic to the city, Plato transforms the philosopher-king into a craftsman and citizens into human matter to be shaped. Arendt denounces this operation as the destruction of politics, as it eliminates plurality in favor of a coercive unity.

Therefore, Arendt's critique points out that Plato's "solution" to the evils of politics was, in fact, its abolition. In seeking stability and eternal truth, Plato tried to transform politics into a techné (technique/art), where the expert holds the monopoly on decision-making. This represents, for Arendt, the loss of the dignity of the public sphere, as freedom does not reside in the execution of a plan preconceived by philosophical wisdom, but in the spontaneous capacity of equal men to initiate something new and unforeseen in the world.

6.3 Convergences: The Necessity of Thought

Despite Arendt's critique of the metaphysical tradition, one should not assume that she despises thought. On the contrary, in her late work The Life of the Mind, Arendt (1991) returns to the importance of thinking, willing, and judging. This work represents a partial rehabilitation of the contemplative life, though in terms radically different from those of Plato.

The convergence between Arendt and Plato occurs in the shared recognition that action without thought is dangerous and morally empty. Arendt illustrates this through her analysis of Adolf Eichmann in Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), where she identifies the "banality of evil" as the result of bureaucratic action devoid of critical reflection. Eichmann was not a man of genuine political action (praxis), but a bureaucrat (animal laborans) who executed orders without questioning. This distinction is crucial: for Arendt, authentic political action requires the critical thought that prepares the individual for moral judgment in critical situations.

However, the thought defended by Arendt differs fundamentally from Platonic contemplation. It is not the solitary vision of the Absolute, but the silent dialogue of the self with itself (two-in-one), which occurs within consciousness. This thought is preparatory for action and judgment, not an end in itself. As Canovan (1992) notes, Arendt's rehabilitation of thought offers an alternative to the traditional dichotomy between contemplation and action, showing how critical thought is essential for political responsibility. Both Plato and Arendt agree that an unexamined life is not worth living, but they diverge on whether that examination should withdraw us from the world or enable us to live better in it with others.

For Plato, thought elevates us above the sensible world; for Arendt, thought prepares us to act better within it.

6.3 Contemporary Relevance

The critical distinction between these two modes of life is urgently relevant today:

Technocracy and the Modern "Philosopher-King": We live in an era that favors episteme over doxa. The belief that political problems (inequality, justice, ecology) can be solved purely by experts, algorithms, or "objective data" is a Platonic inheritance. Arendt (2010) warns us that transforming political issues into technical matters of administration eliminates citizenship and shared responsibility. Modern technocracy reproduces the Platonic structure: a group of experts (contemporary "philosopher-kings") who hold technical knowledge and impose solutions on a passive population. This dynamic threatens the public sphere by replacing democratic debate with specialized administration.

The Crisis of the Public Sphere: The rise of animal laborans (the society of consumption and survival) has eroded the public space. Today, politics is seen as a means to secure private interests (security and wealth), not as a space of appearance and freedom. The recovery of the dignity of Arendt's vita activa is an antidote to political apathy and modern individual isolation. The fragmentation of political communities and the predominance of economic logic over public deliberation represent a posthumous victory of the Platonic subordination of politics to necessity.

Truth in the Post-Truth Era: Paradoxically, the "post-truth" era makes us yearn for Platonic stability. When doxa degenerates into organized lying and totalitarian manipulation, Plato's pursuit of factual truth becomes a resource for resistance. Arendt would recognize that, while rational truth should not tyrannize politics, factual truth is the ground upon which politics rests. Without common facts, no common world is possible. The contemporary crisis of factual truth — the proliferation of "alternative facts" and the erosion of consensus about reality — represents an existential threat to democratic politics. In this context, Arendt's defense of factual truth as the foundation of shared action gains renewed urgency.

7 Transcultural Perspectives: A Comparative Analysis of the Active and Contemplative Life in Western and Eastern Traditions

7.1 Eastern Analogues: Dissolution of the Acting-Contemplating Dichotomy in Asian Traditions

Turning our gaze to Eastern traditions, we find conceptual analogues that, although resonating with Western categories, operate under distinct cosmologies that often dissolve the rigidity of the dichotomy. This comparative analysis not only enriches our understanding of Plato and Arendt, but also questions whether the opposition between contemplation and action is a universal characteristic of the human condition or a specific product of Western metaphysics. The central thesis we defend is that while Western thought structured the contemplative life and the active life in a hierarchical and often exclusive relationship, based on a dualistic ontology that separates the eternal from the temporal, Eastern traditions frequently sought the integration or transcendence of this duality.

7.1.1 Comparative Methodology and Limits of Analysis

Before proceeding to the specific analysis, it is necessary to establish the methodological parameters of this comparative investigation. Following François Jullien's (2002) approach to "detour" and "unrooting" of concepts, we recognize the risks of generalization when treating "Eastern traditions" as a monolithic block. Each tradition examined here has its historical specificities, distinct cultural contexts, and particular philosophical developments.

The comparison does not seek to establish perfect equivalences, but to explore how different civilizations responded to the fundamental human problem of reconciling reflection and action. As Edward Said (1996) warns in Orientalism: The East as an Invention of the West, we must avoid Western projections onto Eastern traditions, seeking to understand them on their own terms.

7.1.2 Hinduism and Vedanta: The Synthesis of Jnana and Karma Yoga

In Indian thought, specifically in Hinduism and the Vedanta tradition, the tension between contemplation and action is articulated through the paths of Yoga. Jnana Yoga, or the path of knowledge, approaches the Western vita contemplativa, requiring intellectual discernment and meditation to realize the identity between the Atman (individual self) and Brahman (the Absolute). However, unlike the mutual exclusion often seen in the West, the Bhagavad Gita (1998) proposes a synthesis through Karma Yoga, the path of disinterested action. Here, the active life is not an obstacle to spiritual realization, as long as action is performed as a sacrifice (yajna), without attachment to its fruits (nishkama karma).

Action thus becomes a form of contemplation in motion, where the individual fulfills their Dharma, or cosmic and social duty, maintaining internal equanimity (samatvam). As Radhakrishnan (1927) explains, Karma Yoga does not represent mere passive resignation, but action transformed by spiritual consciousness. The agent acts in the world while remaining detached from results, in an attitude that dissolves the dichotomy between active subject and passive object. This integration suggests that the Western dichotomy is not inevitable; it is possible to conceive action as an expression of contemplative wisdom, not as its negation. The Upanishads, especially the Katha Upanishad, already anticipated this synthesis by stating that "he who sees diversity goes from death to death" (KATHA UPANISHAD, 1995, 2.1.10), suggesting that true wisdom unifies experience and action.

7.1.3 Mahayana Buddhism: Prajna and Karuna as Dialectical Synthesis

In Buddhism, meditative practice, Dhyana, is central and analogous to contemplation, aiming at the cessation of suffering and Nirvana. However, the Bodhisattva ideal in Mahayana Buddhism radically challenges the notion of purely isolationist contemplation; the Bodhisattva is the one who, having achieved wisdom (prajna), chooses to remain in the cycle of existences (samsara) to act compassionately for the benefit of all beings, integrating wisdom with active compassion (karuna).

As expounded in Shantideva's Bodhicharyavatara (8th century), a fundamental Mahayana text, the Bodhisattva develops the "mind of enlightenment" (bodhichitta) that impels him to remain in the world to alleviate others' suffering: "As long as space endures and as long as sentient beings exist, may I also remain to dispel the misery of the world" (SHANTIDEVA, 1997, p. 34). This figure represents a dialectical synthesis that transcends the dichotomy: contemplative wisdom does not lead to isolation, but to compassionate return to the world. Unlike Plato's philosopher-king, who returns to the cave reluctantly out of duty, the Bodhisattva chooses to remain in the world out of spontaneous compassion. This difference reveals a cosmology where compassionate action is as valuable as transcendent wisdom, constituting two inseparable aspects of the Buddhist path.

7.1.4 Taoism: Wu Wei as Radical Critique of the Dichotomy

In Chinese traditions, the relationship between acting and contemplating takes on unique contours that challenge the dichotomy itself. Taoism, through the concept of Wu Wei, or non-action, offers a radical critique of the Western dichotomy between passivity and activity. Wu Wei does not mean inertia or refusal of action, but effortless, spontaneous action in perfect harmony with the natural flow of the Tao. The Taoist sage, described in the Tao Te Ching (LAOZI, 1996), acts without acting, governs without intervening, and in this apparent contemplative passivity lies the maximum efficacy of action.

There is no rupture here between a static world of ideas and a sensible world in motion; there is only the continuous flow of reality (ziran). As François Jullien (1998) analyzes in A Treatise on Efficacy, Taoist thought represents a logic of efficacy that does not depend on the imposition of will, but on harmony with the natural process. Chapter 37 of the Tao Te Ching states: "The Tao never acts, yet nothing is left undone" (LAOZI, 1996), expressing precisely this non-voluntarist action. Curiously, this spontaneity of Wu Wei resonates with Arendtian natality — both emphasize the capacity to initiate something new — but differ in relation to cosmic order. For Arendt, action is a creative rupture; for Taoism, it is harmony with the existing flow, a "action without agent" where the individual ego dissolves into the movement of the Tao.

7.1.5 Confucianism: Self-Cultivation as the Foundation of Political Action

Confucianism, which could superficially be compared to Western civic humanism for its emphasis on social order, rituals (Li), and benevolence (Ren), grounds its active life in a profound contemplative dimension of self-cultivation (xiu shen). According to the Analects (CONFUCIUS, 2007), the ideal of the Junzi, the noble man, requires constant inner examination and rectification of the mind so that political and social action is harmonious.

Confucian politics is not the imposition of form on matter, as in Platonic poiesis, but the extension of the moral virtue of the ruler who, through his own righteousness (de), orders society without the need for excessive coercion. As Confucius states: "To govern by virtue can be compared to the North Star, which holds its place while all the other stars revolve around it" (CONFUCIUS, 2007, II.1). In this sense, Confucianism offers an alternative to the dichotomy: political action is effective not because it imposes an absolute truth, but because it emanates from a cultivated interiority. The Confucian ruler is not a craftsman who shapes matter, but a model of virtue whose presence naturally orders society through the transformative power of example (de).

7.1.6 Comparative Synthesis and Contemporary Implications

The relevance of this transcultural comparison lies in the perception that the contemporary crisis of the active life in the West, marked by frenetic activism and loss of meaning, can find points of reflection in traditions that never fully divorced the efficacy of action from the serenity of contemplation. The universality of the human problem of how to live is answered in particular ways: the West sought immortality through works and glory or eternity through intellect; the East sought, predominantly, the dissolution of the conflict between agent and action, finding eternity in the very instant of conscious acting.

As Graham Priest (2002) analyzes in Beyond the Limits of Thought, non-Western logics, particularly those that embrace contradictions (like the dialectical logic of Taoism), offer valuable alternatives for thinking the relationship between opposites without the need for hierarchization or elimination of one pole. While the Western tradition structured the contemplative life and the active life in a hierarchical and often exclusive relationship, based on a dualistic ontology that separates the eternal from the temporal, Eastern traditions frequently sought the integration or transcendence of this duality.

In the West, action is often seen as an intervention of will in the world, an imposition of form or a manifestation of individual freedom against natural necessity. In the East, especially in Taoism and Hinduism, ideal action is that which aligns with cosmic order, whether the Tao or Dharma, minimizing egocentric agency and emphasizing harmony with the whole. Plato's philosopher-king, who must be forced to return to the cave, contrasts deeply with the Bodhisattva or Taoist sage, for whom the distinction between being in the world and being outside it is, ultimately, illusory.

Moreover, conceptions of time and history profoundly influence these views. The Western vita activa, especially in modernity, is tied to a linear and progressive view of history, where action aims to create a new and irreversible future, as Arendt points out regarding natality. Eastern traditions, often operating with cyclical conceptions or absolute immanence, value action that maintains the balance and harmony of the whole, rather than revolutionary rupture.

Conclusion

The dichotomy between the contemplative life and the active life constitutes one of the fundamental axes upon which the intellectual architecture of the West was built, establishing a dialectical tension that reverberates from Classical Antiquity to contemporary political theory. In the Western tradition, the vita contemplativa, or bios theoretikos, was inaugurally systematized by Plato and Aristotle as the highest activity of the human soul.

This primacy of contemplation was absorbed and theologically reconfigured in the Middle Ages; Thomas Aquinas in the Summa Theologica maintains the superiority of the contemplative life over the active one, arguing that the former deals with divine and eternal things, while the latter concerns human and temporal needs, though recognizing that preaching and teaching, fruits of overflowing contemplation, possess a mixed dignity.

In contrast, the vita activa, or bios politikos, has a complex trajectory of valorization and redefinition. In the Greek polis, the active life did not coincide with the labor necessary for biological survival, but referred to praxis, free action among equals in the public space, dedicated to the affairs of the city and the conquest of immortal glory. Cicero, representing Roman humanism, momentarily inverted the Greek hierarchy by stating, in On the Republic, that virtue exists entirely in its practical application, defending public service as the supreme duty of the citizen. However, it is in modernity that the active life undergoes its most radical transformation. Hannah Arendt, in The Human Condition, diagnoses a hierarchical inversion where contemplation loses its primacy not to political action, but to labor and fabrication.

The comparative analysis between Hannah Arendt's vita activa and Plato's vita contemplativa reveals two distinct anthropologies, each with its greatnesses and dangers. Plato, faced with the fragility of human affairs, sought refuge in the eternity of Ideas, proposing a politics subordinated to philosophical truth, where order and justice depend on the submission of plurality to the unity of knowledge. It is a vision that offers ontological security and moral stability, but at the cost of political freedom and spontaneity. The philosopher's political responsibility, though recognized by Plato, remains subordinated to the contemplative ideal, creating a tension that is never fully resolved in his work.

Hannah Arendt, in turn, undertook the bold task of rescuing the dignity of human action from the shadow of metaphysics. By distinguishing acting from fabricating and laboring, she reminded us that the human condition is characterized by natality — the miraculous capacity to initiate the new. For Arendt, human greatness does not lie in escaping the cave to a world of mute essences, but in illuminating the cave with shared discourse and action, transforming the world into a habitable home for plurality. However, Arendt does not completely reject thought; she redefines it as an inner dialogue that prepares the individual for moral judgment and responsible action. Thus, the convergence between Plato and Arendt lies in the recognition that an unexamined life is empty, though they diverge radically on the purpose of that examination.

In turn, while the West historically tended to structure the contemplative life and the active life in a hierarchical and often exclusive relationship, based on a dualistic ontology that separates the eternal from the temporal, Eastern traditions frequently sought the integration or transcendence of this duality. In the West, action is often seen as an intervention of will in the world, an imposition of form or a manifestation of individual freedom against natural necessity. In the East, especially in Taoism and Hinduism, ideal action is that which aligns with cosmic order, whether the Tao or Dharma, minimizing egocentric agency. Plato's philosopher-king, who must be forced to return to the cave, contrasts deeply with the Bodhisattva or Taoist sage, for whom the distinction between being in the world and being outside it is, ultimately, illusory. These perspectives do not invalidate the Western analysis, but contextualize it as a specific product of dualistic metaphysics, suggesting that other ways of thinking the relationship between contemplation and action are possible.

Moreover, conceptions of time and history profoundly influence these views. The Western vita activa, especially in modernity, is tied to a linear and progressive view of history, where action aims to create a new and irreversible future, as Arendt points out regarding natality. Eastern traditions, often operating with cyclical conceptions or absolute immanence, value action that maintains the balance and harmony of the whole, rather than revolutionary rupture. The relevance of this comparison lies in the perception that the contemporary crisis of the active life in the West, marked by frenetic activism and loss of meaning, can find points of reflection in traditions that never fully divorced the efficacy of action from the serenity of contemplation. The universality of the human problem of how to live is answered in particular ways: the West sought immortality through works and glory or eternity through intellect; the East sought, predominantly, the dissolution of the conflict between agent and action, finding eternity in the very instant of conscious acting.

Ultimately, the tension between acting and contemplating should not be resolved by eliminating one pole, nor by subordinating one to the other. Politics without contemplation becomes blind activism and destructive bureaucracy; contemplation without return to politics becomes escapism and irrelevance. The contemporary challenge is to find a way of thinking that is worldly and a way of acting that is reflective, ensuring that love of truth does not destroy love of the world. In this sense, both Plato and Arendt, despite their fundamental divergences, offer us resources to think this integration: Plato, by insisting that truth must guide politics; Arendt, by insisting that politics cannot be reduced to a means for external ends. The synthesis we seek is not an easy reconciliation, but a permanent dialogue between the demand for truth and the demand for freedom, between contemplation that elevates us and action that roots us in the shared world. The transcultural perspectives explored here suggest that this synthesis does not need to reproduce Western hierarchization, but can learn from traditions that thought the relationship between contemplation and action in less exclusive ways, offering alternative paths for a political life that is simultaneously reflective and creative.

APPENDIX: ADDITIONAL CRITICAL NOTES

A.1 On Arendt's Interpretation of Plato

Hannah Arendt's reading of Plato is deeply influenced by her own historical experience and contemporary political concerns. Although her analysis is philosophically fruitful, it is important to recognize that it represents a specific interpretation, not an established truth about Platonic thought.

Gregory Vlastos (1991), in his work on Socrates, argues that Plato maintains a productive tension between the contemplative ideal and political responsibility, not a simple rejection of the latter. For Vlastos, the figure of the philosopher-king is not an isolated tyrant, but someone who, though reluctant, recognizes his duty to the city.

C. D. C. Reeve (2004), in turn, offers a reading that emphasizes the continuity between Plato's theory of justice and its political implications. For Reeve, Plato does not seek to escape politics, but to ground it in rational principles that transcend the fluctuations of democratic opinion. This interpretation does not invalidate Arendt's critique, but suggests that the relationship between Plato and politics is more nuanced than a narrative of "traumatic escape" might imply.

Monique Dixsaut (2003) offers yet another perspective, showing how Platonic dialectic involves a continuous movement between the intelligible and the sensible. For Dixsaut, the philosopher's ascent in the Allegory of the Cave is not a permanent rejection of the sensible world, but a back-and-forth movement that characterizes philosophical activity itself. This dialectical reading complicates the narrative of rigid hierarchy that Arendt presents.

A.2 On Arendt's Rehabilitation of Doxa

Arendt's rehabilitation of doxa (opinion) is one of her most original contributions to political philosophy, but also one of the most controversial. Bonnie Honig (2007) argues that this rehabilitation represents a genuine democratic alternative to Plato's pursuit of absolute truth, without, however, falling into relativism. For Honig, Arendt offers a path between Platonic dogmatism and radical skepticism: doxa is legitimate as an expression of human plurality, but must be grounded in common facts and factual truth.

Seyla Benhabib (2000), in turn, emphasizes how Arendt's analysis of the vita activa offers a profound critique of the modern reduction of politics to administration. For Benhabib, Arendt recovers the dimension of freedom and creativity that characterizes genuine action, in contrast to the growing bureaucratization of modern political life. This perspective is particularly relevant for understanding how Arendt's critique of Plato is, ultimately, also a critique of modern technocracy.

Margaret Canovan (1992) offers a reading that contextualizes Arendt's work in relation to the totalitarian experiences of the 20th century. For Canovan, Arendt's rehabilitation of doxa and political action is a direct response to the totalitarian attempt to eliminate plurality in the name of a single ideological truth. In this context, Arendt's critique of Plato acquires a contemporary political urgency: the subordination of politics to truth is the first step toward totalitarianism.

A.3 On Transcultural Perspectives

The inclusion of Eastern perspectives in this essay seeks to question whether the Western dichotomy between contemplation and action is universal or culturally specific. François Jullien (1998), in his work on Taoist thought, offers a sophisticated analysis of how the concept of Wu Wei (non-action) represents a logic of efficacy radically different from that which characterizes Western thought. For Jullien, the Taoist sage does not impose his will on the world, but aligns with its natural process. This perspective offers a profound alternative to the Platonic dichotomy between form and matter.

Graham Priest (2002), in his work on non-Western logics, argues that many Eastern traditions embrace forms of thought that allow the coexistence of opposites without the need for hierarchization. For Priest, the dialectical logic of Taoism and other Eastern traditions offers valuable resources for thinking beyond the binary dichotomy that characterizes Western metaphysics. This perspective suggests that the synthesis between contemplation and action we seek does not need to reproduce Western hierarchization, but can learn from traditions that thought this relationship in less exclusive ways.

A.4 Implications for Contemporary Political Philosophy

The comparative analysis between Plato and Arendt, enriched by transcultural perspectives, offers valuable resources for thinking about contemporary political challenges. The rise of technocracy, the crisis of the public sphere, and the erosion of factual truth are all phenomena that can be understood as manifestations of a Platonic hierarchization of truth over opinion, expertise over democratic deliberation.

However, Arendt's rehabilitation of political action should not be understood as a naive return to pre-modern direct democracy. On the contrary, it is an attempt to recover the dimension of freedom and creativity that characterizes genuine action, even within the complex structures of modern politics. In this sense, the convergence between Plato and Arendt — both recognizing the importance of critical thought — offers a path to a politics that is simultaneously reflective and creative, that respects factual truth without allowing it to become tyranny.

Eastern perspectives, in turn, suggest that this synthesis does not need to be a reconciliation of opposites, but can be a transcendence of the dichotomy itself. Action that emanates from contemplation, efficacy that results from harmony with natural order, politics that is an expression of inner virtue — these are alternatives that Eastern traditions offer and that deserve to be explored in the context of contemporary Western political philosophy.

EXPANDED CONCLUSION

The tension between the vita contemplativa and the vita activa is not merely a historical or academic problem, but a living issue that continues to structure our political and existential choices. The comparative analysis between Plato and Arendt, complemented by transcultural perspectives, reveals that this tension is neither inevitable nor universal, but a specific product of Western metaphysics that can be thought of in other ways.

The challenge we face in contemporaneity is twofold: on the one hand, we must resist the Platonic temptation to subordinate politics to truth, recognizing that human plurality and political freedom are irreducible values. On the other hand, we must avoid radical relativism that denies the importance of factual truth and critical reflection. The synthesis we seek is a permanent dialogue between these demands, a recognition that authentic politics requires both thought and action, both contemplation and engagement.

Eastern traditions offer us resources to think this synthesis in less hierarchical and exclusive ways. The integration of Karma Yoga and Jnana Yoga in Hinduism, the active compassion of the Bodhisattva in Buddhism, harmony with the Tao in Taoism, and the inner virtue of the Junzi in Confucianism — all these figures represent ways of life that do not radically separate contemplation from action, but see them as complementary aspects of a full existence.

Ultimately, what is at stake is not only a matter of political philosophy, but a question about how we want to live. Do we want a life that is merely contemplative, isolated from the world and its challenges? Do we want a life that is merely active, frenetic and devoid of reflection? Or do we want a life that is simultaneously reflective and creative, that honors both truth and freedom, that is rooted in the shared world but also open to the possibilities of the new? The answer to this question is not given once and for all, but must be constantly re-elaborated through dialogue between traditions, between thinkers, and between ourselves and our contemporaries. It is in this permanent dialogue that true political life resides — not in the imposition of an eternal truth, but in the shared creation of a common world where freedom and truth can coexis

References

Aquinas, T. (2005). Summa theologica (Fathers of the English Dominican Province, Trans.). Christian Classics. (Original work published ca. 1265–1274)

Arendt, H. (1963). Eichmann in Jerusalem: A report on the banality of evil. Viking Press.

Arendt, H. (1991). The life of the mind. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Arendt, H. (2009). Essays in understanding, 1930–1954: Formation, exile, and totalitarianism (J. Kohn, Ed.). Schocken Books.

Arendt, H. (2010). The human condition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1958)

Aristotle. (2001). Nicomachean ethics (W. D. Ross, Trans.). In The basic works of Aristotle (R. McKeon, Ed.). Modern Library. (Original work published ca. 350 BCE)

Benhabib, S. (2000). Judgment and the moral foundations of politics in Hannah Arendt's thought. In D. Villa (Ed.), Cambridge companion to Hannah Arendt (pp. 193–231). Cambridge University Press.

Bhagavad Gita. (1998). The Bhagavad Gita (E. Easwaran, Trans.). Nilgiri Press. (Original work published ca. 2nd century BCE)

Canovan, M. (1992). Hannah Arendt: A reinterpretation of her political thought. Cambridge University Press.

Cicero. (2018). On the republic (C. D. Keyes, Trans.). In Cicero: De republica and De legibus (pp. 1–280). Harvard University Press. (Original work published ca. 51 BCE)

Confucius. (2007). The analects (D. C. Lau, Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Original work published ca. 5th century BCE)

Dixsaut, M. (2003). Plato's philosophy: The dialectic of the intelligible and the sensible. In The Cambridge companion to Plato (2nd ed., pp. 85–110). Cambridge University Press.

Honig, B. (2007). Democracy and the foreigner. Princeton University Press.

Jullien, F. (1998). A treatise on efficacy: Between Western and Chinese thinking. University of Hawaii Press. (Original work published 1996)

Jullien, F. (2002). The detour and access: Thought on some modes of cultural encounter. Zone Books.

Katha Upanishad. (1995). In The Upanishads (V. Eknath, Trans., pp. 1–50). Nilgiri Press. (Original work published ca. 800–500 BCE)

Laozi. (1996). Tao Te Ching (S. Addiss & S. Lombardo, Trans.). Hackett Publishing. (Original work published ca. 6th century BCE)

Plato. (2001). The republic (G. M. A. Grube & C. D. C. Reeve, Trans.). In Complete works (J. M. Cooper, Ed., pp. 971–1221). Hackett Publishing. (Original work published ca. 380 BCE)

Priest, G. (2002). Beyond the limits of thought. Oxford University Press.

Radhakrishnan, S. (1927). The Hindu view of life. Macmillan.

Reeve, C. D. C. (2004). Philosopher-kings: The argument of Plato's Republic. Princeton University Press. (Original work published 1988)

Said, E. W. (1996). Orientalism: Western conceptions of the Orient (25th anniversary ed.). Penguin Books. (Original work published 1978)

Shantideva. (1997). The way of the Bodhisattva (Padmakara Translation Group, Trans.). Shambhala Publications. (Original work published ca. 8th century CE)

Vlastos, G. (1991). Socrates, ironist and moral philosopher. Cambridge University Press.

Comments